With increasing heat and drought across the West, one of the largest tree die-offs in modern California history reached new heights last year and, in combination with wildfires, has left much of the state’s once sprawling green forests browned, blackened and in critically dire shape.

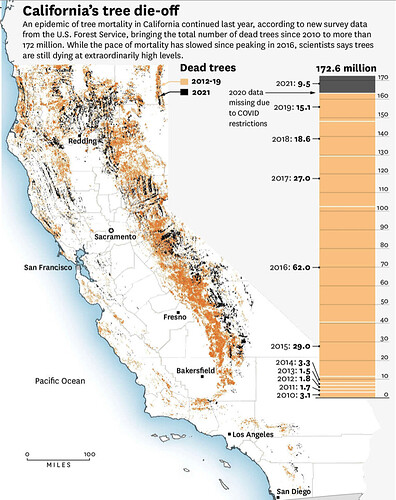

An estimated 9.5 million trees died from bugs, disease and dehydration in 2021, according to new aerial survey data from the U.S. Forest Service. The losses were slightly less than what was recorded in surveys two years earlier but still well above what scientists consider normal. The run of mortality since 2010 now exceeds 172 million trees.

The epidemic, which started last decade in the southern Sierra Nevada and has since spiraled throughout the state, is contributing to the changing character of California’s 33 million acres of forests. The timberland, notably conifer forest, has become increasingly prone to losing biodiversity, giving way to encroaching shrubs and grasslands, and burning up in wildfire.

Big Sale. Great Deal. | Get an Entire 12 Weeks of Access for 99¢

ACT NOW

Already, dead pines and firs and have provided fodder for scores of fires, and in doing so, compounded the increase in tree mortality. Last year alone, a few hundred million trees may have died from flames in California, according to burn severity data from the Forest Service.

“Our forests are at mortal peril,” said Hugh Safford, a recently retired Forest Service regional ecologist and now chief scientist at Vibrant Planet, a company that works on climate issues. “They are absolutely at mortal peril.”

Beyond the harm done to the flora and fauna of the forest, the die-off threatens to blunt many of the benefits that these wildlands provide, such as supplying clean water, producing high-quality timber and absorbing carbon to help limit global warming.

“To me, the only question is if we can get our (act) together in time (to save the forest),” Safford said.

A leading cause of the die-off is the changing climate. Frequent drought over the past decade, much of it tied to warming temperatures, has not only created conditions ideal for fire, but also has weakened trees and made them more susceptible to insect infestation and disease.

The tens of millions of dead trees counted in the Forest Service surveys, which do not include burned trees, are often deprived of water to the point where they can no longer survive adversity, the main foe being bark beetles.

Making matters worse, scientists say, is the overcrowding of California’s forests. A century-old policy of fighting wildfires, instead of allowing them to burn, has thwarted a natural process of forest thinning. The subsequent build-up of vegetation has created both a dangerous amount of tinder for fire and a situation detrimental to the health of the trees.

More for you

California slips into its worst mega-drought in 1,200 years — it’s partly our fault

Storm took a big toll on Bay Area trees. Did the drought make them more vulnerable?

“The forest is in such a high density and is facilitating mortality because the trees can’t live when they’re competing with their neighbors,” said Scott Stephens, a professor of fire science and ecologist at UC Berkeley. “They’re just not able to weather episodes of difficulty anymore.”

Last year, in the southern and central Sierra and as far north as Lake Tahoe where lifeless trees blanket mountainsides in deathly apricot hues, the epidemic continued, with significant losses in Fresno and Tulare counties, according to the Forest Service survey data.

The most concerning toll, though, was even farther north, where dead trees — hard to find just a few years ago in the much moister terrain — now pepper the slopes of the Klamath, Trinity and northern Sierra ranges. Siskiyou County recorded the most deaths of any county in 2021, with about 10% of the total.

“The Northern California forests have not had the episodes of mortality that we’ve seen in the south, but if we have continued drought in the north, we’re going to see the same, which is very worrisome,” Stephens said.

Nearly two-thirds of the trees that died in 2021 were firs, often infested with fir engraver beetles, according to the survey data. Sugar and ponderosa pine, early victims of the die-off, also continued to perish, largely because of mountain and western pine beetles.

In the East Bay, an unusual routing of 75,000 hardwood trees was recorded last year, which included acacia and eucalyptus. Scientists studying the deaths believe it may be the work of fungi in tandem with drought. Mortality is extensive at the East Bay Regional Park District’s Anthony Chabot, Reinhardt Redwood and Tilden parks.

Dead trees that pose a dangerous wildfire risk as part of a mass die-off dot the landscape in East Bay Regional Park District land in Contra Costa County.

Dead trees that pose a dangerous wildfire risk as part of a mass die-off dot the landscape in East Bay Regional Park District land in Contra Costa County.

Provided by East Bay Regional Park District

The surveys are designed to broadly assess forest conditions on federal, state and private lands in California. They’re conducted annually by planes crisscrossing the state, though a full count of dead trees was not completed in 2020 because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The surveys show that increased tree mortality began at the start of the last decade and peaked at the end of the five-year drought. In 2016, 62 million trees died.

The numbers have since fallen, but they’ve remained much higher than the 1 million annual deaths from age considered typical. If the current year continues to see little precipitation, after two previous dry years, scientists say the pace of loss will inevitably pick up again.

“We’re always hoping for the fabulous February (rain) and the March miracle,” said Sheri Smith, regional entomologist for the Forest Service and one of the managers of the aerial surveys. “But if it ends up dry again, I have no doubt we’ll start to see an increase in tree mortality.”

The drought-driven die-off, observed across 1.3 million acres last year, comes on top of — and is partly responsible for — the havoc that wildfire wreaked on trees in 2021.

While there is no official tally of dead trees across the 2.6 million acres that burned in California, the Forest Service estimates that more than 100 million trees died in the northern Sierra’s Dixie Fire alone. The 963,000-acre blaze may be the most destructive, in terms of trees killed, in California in decades.

“The loss from that fire dwarfs any insect and disease mortality over the past couple of years,” said George Gentry, senior vice president of the California Forestry Association, which represents the timber industry.

Logging companies, as a matter of course, regularly deal with variability and less-than-stellar forest conditions, often removing trees to halt pathogens or harvesting trees before they’re toppled by bark beetles. Gentry, however, says there’s not much that can be done when timberland is completely burned over.

While fire has historically benefited California’s wildlands, helping clear overgrowth and reinvigorate landscapes, many of the recent blazes, like the Dixie Fire, have burned hotter than in the past, making them more destructive than restorative.

Manual tree thinning and intentionally lighting fires to bring back more sustainable conditions remain among the most effective strategies, though such work has been sparse given the scope of the problem.

In January, in what the federal government called a “paradigm shift” to lessen wildfire risk, the Forest Service unveiled plans to spend an additional $655 million in each of the next five years on forestry projects, on top of the roughly quarter million dollars it currently spends annually. California is expected to receive a major chunk of the windfall.

Gov. Gavin Newsom, at the same time, has boosted state spending on fire prevention, recently proposing a $1.2 billion two-year wildfire package that includes $482 million to reduce the buildup of vegetation.

The two governments have agreed to jointly treat 1 million acres of forest in California each year by 2025.

“I’m mildly optimistic for the first time in my career,” said Malcolm North, a research ecologist with the Forest Service and professor of plant sciences at UC Davis, who has long advocated for more tree removal and prescribed burning.

North, however, said that while commitments from state and federal authorities will help lessen fire danger, at least somewhat, more work will be needed to help forests withstand forces of drought, disease and insect infestation.

“Wildfire is not the only problem we’re facing,” he said. “If you want to make the forests able to survive these other stressors with climate change, you really have to reduce competition among the trees.”

A new scientific paper authored by North, with help from several others including Stephens at UC Berkeley, calls for removing as much as 80% of the trees in parts of California’s forests. The seemingly hawkish target, outlined in the journal Forest Ecology and Management, is based on the premise that this is how much vegetation needs to be cleared to give trees the space they need to grow strong and resilient.

The research cites timber surveys from 1911, before modern forestry and wildfire suppression, that found forests were six to seven times less dense than they were a century later, with trees twice as big.

The study’s recommendations, though, have not been universally welcomed. Some suggest that the level of clearing proposed is excessive and would result in widespread disturbance to forests, notably wildlife, as well as unleash damaging amounts of carbon from trees into the atmosphere.

Chad Hanson, a research ecologist and co-founder of the nonprofit John Muir Project who is skeptical of forest interventions, downplays the severity of the tree die-off. He says big swaths of mortality in the Sierra provide unique habitat for birds, insects and other animals and have long been part of the natural process.

“It’s good to have a mix of live trees and dead trees,” Hanson said. “It’s about where that mix is.”

Most researchers, though, believe the equilibrium of the forest is wildly off. North and others, noting that current forest management policies aren’t working, insist big changes are needed to protect California’s wildlands, both for their intrinsic value and their value to people.

“There’s a whole suite of ecosystem services associated with forests,” North said. “It’s really important to hold on to those.”